Northern Ireland - the home of Rachel ELDON and James FOX |

|

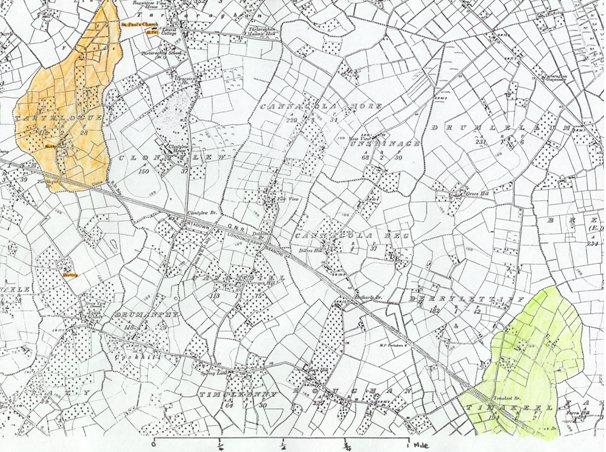

(This is a repeat of information in the ELDON link) What was Ireland like when Rachel Eldon was growing up there on her father's farm? I have been lucky enough to find some valuable books to give me answers to this question: one is Ordnance Survey, Memoirs of Ireland, Parishes of County Armagh and the other is The Famine in Ulster by Christine Kinealy and Trevor Parkhill. The land of Ireland was divided up in several different ways. First of all there are the Provinces; there are four of these - Munster, Leinster, Connaught and Ulster. Ulster contains nine counties; six of these being in what today is called Northern Ireland and three of them being in Ireland or Eire. Northern Ireland is still part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and is often referred to as Ulster but this is not strictly speaking correct. Then there is a further division into counties; there are six of these in Northern Ireland. The Counties used to be divided again into Baronies, which were named after the most important landowner in the area, but these have now fallen into disuse. The next division was into parishes and they, and the smallest administrative division of townlands, are still in use. The word `townland' is a misnomer and arose from a mistranslation of the Gaelic words baile fearainn which actually means `homestead land' but the word baile later had a secondary meaning `village' town' or `city'. So townlands have nothing what-so-ever to do with a town; they are a collection of a few small farms. The size of Townlands varies between 50 and 500 acres so they are very small divisions indeed. From the marriage certificate of Rachel Eldon and James Fox, we find that Rachel came from the townland of Tarthlogue and James from the townland of Timakeel and that they were married in the parish church of Tartaraghan in the county of Armagh. The Barony for this was Oneilland, the O'Neil family having previously been the largest landowners and most important family in the area. Armagh was in the part of Ulster which is now Northern Ireland. Both of the townlands are about three quarters of a mile by a third of mile in size and are divided up into very small farms. Tartaraghan and Kimakeel are a little less than two miles apart. There is no smithy in Timakeel marked on the map but there is one in Tarthlogue so perhaps James had come to work in Tarthlogue and met Rachel there. The Irish people love to lavish names on their land and there is scarcely a rock or clump of trees that goes unnamed. Each of the fields comprising a farm has its own name, e.g. the river field, the chapel field, the road field, the coursing field, the bush field, the nine acres and so on. In the book of Memoirs of Ireland, Parishes of County Armagh, which was written to accompany the Ordnance Survey maps of Ireland, there is a very detailed description of the parish of Tartaraghan, its scenery, its people, their occupations, the climate and the crops for 1835 and 1837. At this time Rachel Eldon would have been 8 to 10 years old. The parish of Tartaraghan was situated in the northern part of the county of Armagh and in the barony of Oneilland West. It is bounded on the north by Lough Neagh and its extreme length is six miles and the breadth five and a half miles (approximately 11,612 acres). Of this the northern part (two miles long and two miles wide) is bog. In the bog there were the remains of trees, still standing, and these were used for building material and for fuel. The peat of the bog was also a very valuable fuel and the process of cutting and drying turf provided employment for a great number of poor people. According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica the bog lands were also used for rough grazing for sheep and cattle. In the bog there were several small hills rising above the main bog and these were cultivated. Possession of land was very important to the Irish people and every available scrap that could be used was used. |

|

|

|

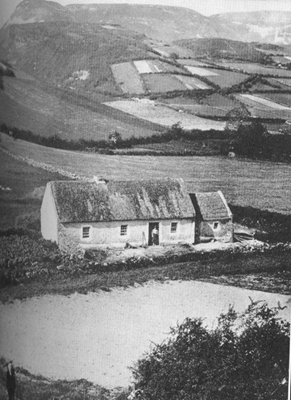

Rachel's father, Joseph Eldon, was a farmer so she was brought up on a farm. The farms were very small, being only from 4 to 40 statute acres. They were held in tenancies from landlords either under leases of 3 lives or for one life of 21 years. The fields on the farms were very small, badly shaped and enclosed with banks of earth. The crops that Joseph Eldon would probably have grown were wheat which was sown in November and reaped in August, barley and oats which were sown in March and reaped in July and August, flax, sown in April and pulled in July, potatoes planted in April and lifted in November. He would probably also have kept a few cows, some sheep and hens. The size of the farms meant that they could not supply a viable living for a family. A second income was very necessary. For many years Ireland has been famous for its linen and most of the flax for it was grown in Ulster. After the crop was harvested and the outer part of the stem allowed to rot, the inner fibres of flax would be sent to the mills to be processed and spun although some was spun by cottagers. It then came back to the farmhouses where the wives of the farmers wove it into cloth. Rachel's mother, another Rachel, would probably have spent a great deal of her time weaving linen and more than likely have taught her daughter some of the skills. A tolerably good weaver earned from 3 shillings to 4 shillings a week and a spinner only from one shilling to one shilling and 3 pence a week. In the book `Ordnance Survey, Memoirs of Ireland' the 1835 account of the parish is different from the 1837 one in some respects. In the 1837 account it says that the cottages were good, being mostly built of stone, whitewashed and thatched. The 1835 account says that the cottages were built of mud. Both accounts said that they were all one storey and consisted at the most of 2 or 3 rooms. Many only had one room. Some of the very small cottages seem to have been rather miserable places. The description given is that they frequently consisted of one very small apartment, the walls of which were built with sods placed upon the bare bog without any flooring, the roof was covered with straw in a very loose manner without any opening for the smoke beyond a small opening in the roof. There was a great want of comfort and cleanliness about them. Potatoes formed nearly the only article of food amongst the lower order of people. Those of the better class had good stone cottages and their diet included oatmeal or milk and butter and occasionally meat. |

|

|

|

A description of the parish scenery said that the southern part

of Tartaraghan (where Tarthlogue and Timakeel were situated) was

picturesque and well cultivated. There were hedges around

fields and some wooded areas. The northern part, near to Lough

Neagh, consisted principally of extensive tracts of bog covered

with heath, which (excepting the islands within the bog) had a

wild and barren appearance. The highest land in the parish was

161 feet.

There were also several churches. They were St Paul's, the Parish Church (Church of Ireland) where Rachel and James were married. It has a Churchyard where several members of the Eldon family are buried. In 1835 the population of the parish was 6300 of which 4020 were of the established church, the Church of Ireland (equivalent to the Church of England), 1880 were Roman Catholics and 300 were Presbyterians. There seems to have been very little in the way of entertainment. The people in the northern part of the parish were said to enjoy dancing and those in the southern part liked to follow the hounds on foot. There was a meet on 3 days of the week during the hunting season. There was no fair or market in the parish but people could go to the ones held in Portadown, Dungannon and Armagh which were not far away. The Fox family that I knew believed that Rachel Eldon was musical and brought a piano out to Australia with her. Whether or not this is true I do not know but it is certainly true that many of her descendants were musically talented so perhaps a piano was kept in the home in Ireland and music was one of the forms of the family entertainment. The Great Famine

The farms had become very small partly owing to the practice of dividing the land up between all the sons in the family and partly because when the family income could be supplemented with the weaving of flax not so much land was needed to keep a family and often some was sold off. With industrialisation and the slump in trade this extra income from flax weaving was taken away and the farmers were struggling to feed their families. Then in 1845 blight caused the failure of much of the potato crop There had been crop failures before . Between the years 1800 and 1845 there had been several crop failures and their subsequent resulting famines. These had been dealt with by traditional providers of relief - clergy, landlords, large farmers - who initiated steps to provide assistance to help the destitute. The difference at the time of the Great Famine was that it was not just for one year. The blight returned to Ireland in 1846 and again in 1847and local relief could not cope with it. In Armagh a workhouse, with a capacity for 500 inmates had been set up in 1841 but by 1846 it was full to over-capacity with 805 inmates and this went on increasing . There was a high dependence on the potato amongst the rural poor of Ulster. It was the staple food of an estimated two fifths of the population. Many people potatoes only, for breakfast, lunch and supper. From every area came harrowing reports of human suffering and the condition of numerous working class people was described as being one of `extreme deprivation and distress'. The consequences of the famine - distress, disease, emigration, evictions and excess mortality - were evident throughout Ulster. In Tataraghan, the parish in which the Eldon and the Fox families lived, the Rev. Clements complained that the area suffered from absentee proprietors and that `a large number of the most wretched tenants are not assisted by the landlord'. Again in Tartaraghan, The Society of Friends, commenting on conditions there said, `Last year, to have been buried without a hearse would have been a lasting stigma to a family; now hearses are almost laid aside'. Mass burials were becoming commonplace. The Society of Friends, in reporting that people were dying of starvation added that one member reported on seeing a four year old girl, `a few weeks ago a strong healthy girl, who was so emaciated as to be unable to stand or move a limb'. Rachel Eldon, born in 1827, would have been in her late teens during the time of the Great Famine. I wonder how much she and her family were effected by it and how much of this misery she saw. None of the Eldon family are reported in the parish burial register as dying at this time so maybe they escaped the worst of it. Maybe they had sufficient land and crops to allow them to keep themselves from the worst of the famine. |