The TOPPERWIEN Family History

Click here to view the TOPPERWIEN Family Tree,

Click here to view the FOX - TOPPERWIEN Family Tree,

|

The connection between the NEWMAN family

and the TOPPERWIEN family was made when Dina NEWMAN married Eldon

FOX whose mother was Ivy May TOPPERWIEN.

Some Topperwien Background History

|

|

The Topperwien family came from the Lanau in the Harz

Mountains in eastern Germany where they had lived for many

generations. Some years ago I was in correspondence with a

member of this family, Annemarie Topperwien, who still lived in

Germany although not in the same area as her ancestors. She sent

me the following piece of writing which was written by her

father-in-law, Heinrich Ernst August Topperwien (born 8th

November 1892, Hertzberg, Germany - died 3rd October 1956,

Solingen, Germany) who was the son of Heinrich Karl Topperwien

and Friederike Soffker. Both men seem to have been known by

their last forenames, August and Karl. The grandmother he speaks

of would have been Dorothee Benhausen.

|

|

Map showing the Harz Mountains where the Topperwien

family lived for many generations.

|

|

EXTRACTS FROM AUGUST TOPPERWIEN'S NOTICES IN THE FAMILY

BIBLE

Translated from the German by Anna Fuchs.

In the middle of the 17th century the iron ore industry in Lonau

came to a standstill [the Thirty Year's War]. In 1667 things

were set in motion again in Lonau. After 1732 the iron smelting

industry centred more on Andreasberg. In 1766 the industry

finally closed down at Lonau but the Lonau foundry (near

Hertzberg) continued to function. It is the latter that must

account for the description of Conrad Topperwien as "coal worker

at the iron works" in 1809. In the village the only sources for

making a living that remained were charcoal burning, timber

felling, animal husbandry and arable farming on a subsistence

level.. Toward the end of the last century coal mining and the

railway almost completely destroyed the charcoal burning

industry. Herman August Topperwien (1833-1892)

[see Topperwien Family Tree] was the last of the

family still to have been employed as a charcoal burner in his

younger years, as from the last third of the last century the

more able of the village youths sought their living and their

fortune in increasing numbers in the wider world; this was also

the case of Karl Topperwien (1861-1903).

Our ancestors have been iron workers, respectively charcoal

burners, since the beginning of time, i.e. for about 300 years.

My great-grandfather and my grandfather were charcoal burners.

The tradition passed down leads to the conclusion that even our

ancestors before these were charcoal burners rather than iron

mine workers. Apart from this at least as long as they lived in

Lonau, they were also small-scale peasants owning about half a

dozen Morgen [about 0.9 acres] of fields and meadows. The work

of looking after the land and the animals was largely left to the

mother and the older children. The husband would only stay at

home when it came to planting the potatoes, to mowing, to lifting

the potatoes and to killing the pigs. Fr. Gunther in his book

"Harz", 1910 gives an excellent description of the trade of

charcoal burning.

|

"While the forestry workers will spend at least one night a week

under the same roof as their families the charcoal burners will

only see their village on very special occasions during the whole

of the summer, half of the year, because the charcoal kilns will

burn on Sundays as much as during the rest of the week. But once

a week the charcoal burner's wife will be on her way with her

wicker basket in order to bring bread, something to eat with the

bread and other supplies to her husband. Since one master's

charcoal clearing usually consists of four to six kilns that are

kept working at any one time but are at different stages, one

visit at one of the clearings will suffice to become acquainted

with all the work of the charcoal burning industry! - Here we are

watching the erection of a kiln: Two poles form the centre of a

circular `coal area', round pieces of timber are placed around

them almost vertically, layer by layer, in such a way that an air

shaft is left between the poles right down to the ground and down

on the ground there remains a horizontal air shaft. In another

place assistants are busy covering a completed kiln construction

about 3 meters in height with twigs and grass and also with a

whole lot of earth and coal dust. Once the kiln is ready the

charcoal burner (master) will set it alight by means of a

folded-up, resin-filled piece of bark that he inserts, with the

help a stick, through the air shaft into the pieces of wood in

the middle of the kiln.

|

|

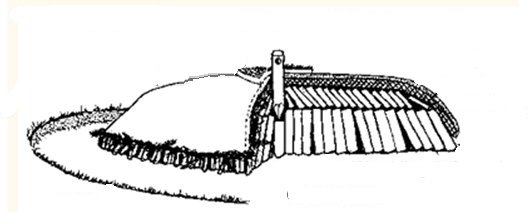

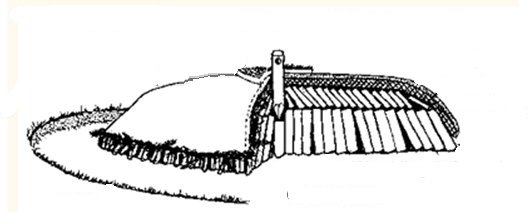

The construction of a charcoal kiln

|

Several kilns are already burning away.

The one with the white-greyish smoke was lit only the day before

yesterday, another one, blue on all sides, has reached the stage

at which the charcoal is already `fermenting'. The control over

the fire, `governance of the fire', is the charcoal burner's

special skill. Quite frequently he has to re-route the wind

shafts and create draft holes on the leeward side of the kilns.

At other times he has to repair cracks in the kiln's covering as

the fire keeps wanting to burn the coverings. For this purpose

he uses a long pole or he will try to heal the cracks by means of

covering them with pieces of turf. The charcoal burner cannot

relax either day or night and - like the captain of a ship - he

has to divide up the time into `watches'.

|

|

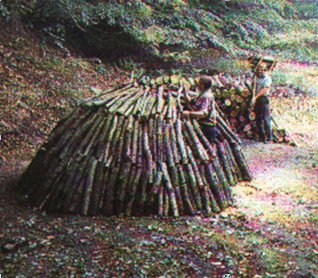

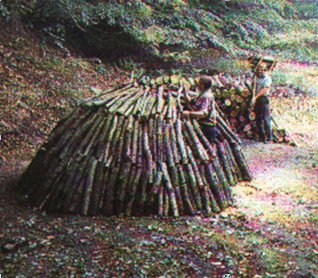

A charcoal kiln in the forest

|

It is a real pleasure to watch the filling up of the burning

kilns in the evenings. You can see the sooty figures enveloped in

smoke, by the light of the brightly burning glow of the coal, as

they handle their material most vigorously on top of the kilns.

For a whole week the kilns must be refilled with wood each day

to the extent to which they have burnt down. The charcoal burner

will lay his `steps' consisting of a thick, long log with

carved-in footsteps against the kiln, he will climb up these

`steps', will shovel away the covering from the sunk-in lid, will

push down the coal with his long pole, will hammer in the wood

that his assistants pass up to him, will then replace the lid

protecting it with further coverings (of ashes and twigs and

moss). All this has to be completed as quickly as possible,

since the longer the kiln is allowed to burn away in the open the

more of the coal will turn to ashes. When the coaling process is

completed the kiln will turn into one glowing mass, a

terrifyingly beautiful sight in the dark night.

The charcoal burner's hovel, his living quarters, is not unlike

that of the forestry worker. Young spruce of the thickness of an

arm are knocked into the ground forming a circular shape. They

are bent at the top to make a conical shape and are covered with

large pieces of bark on the outside, the gaps on the inside are

plugged with moss. A low opening with a small overhang serves as

both door and window; in the middle of this hovel a stone

construction makes a fireplace and there are benches all around

this standing close against the wall. Covered with pine twigs

and moss these benches also make up the sleeping quarters, the

master on the right, his assistants on the left and the boys

somewhere in the background. Several small cupboards contain the

eating provisions. In the evenings the tired workers will camp

around the crackling fire whose smoke tries in vain to escape and

they will prepare their beloved charcoal-burner's soup consisting

of slices of bread, water, salt, pepper and butter; they will

complete their meal with bread and sausage and a sip of brandy.

After this they will make up the fire once more, close the door

and soon it will only be the breathing of the sleepers that will

intercept the silence and loneliness of the forest.

The `Hillebille' (alarm), a beech plank and a wooden hammer fixed

between two trees, that in the old days used to serve the

charcoal burner to assemble his comrades for meals from distant

kilns and also as an alarm signal to gather all men of the same

trade from considerable distances has not been in use for a long

time.

The charcoal burner whose loneliness is usually shared by a

shaggy dog is on the most friendly terms with the animals of the

forest. The shy deer will play happily within his vicinity and

the careful stag will trot through the smoke of the kiln without

special concern."

|

|

|

The Topperwien House.

The oldest house known to have been

inhabited in Lonau by a member of our family was the one directly

on the left of the church, building No 75. It was still

inhabited by Heinrich Christoph Topperwien (1752-1817). The

third of the building facing the church was only added in the

eighties of the last century. Ever since the days of Heinrich

Christoph's son, Heinrich Conrad (1788-1871), our family has been

living in `am Wasser', that is by the Lonau [River], house No 21.

The author (of these extracts) spent almost all his holidays in

that house until the death of his grandmother (1908), his Lonau

playmates would, therefore, call him `water August' (as in fact

his father had always been nicknamed `water Karl'.

|

|

Typical village houses in the Harz Mountains

|

He maintained the peasant style of the house, in inextinguishable

memory; the back of the house (with sturdy settee, the simple

blue food cupboard on the inside of the door of which the

grandmother had noted important dates in chalk, with the table

that contained a box for the preparation of cheese below its

removable top); the living room in which he so often sat with the

grandmother taking the evening meal by the light of the paraffin

lamp and then listening to the hum of the spinning wheel and

trying to get the laconic lady to talk about old times - and on

one occasion, but on one occasion only, he got the hard, surly

lady to sing a song from the time of her youth `In des garten

dunkler Laube', the Sunday-room, in which the sun's rays would

play all day long on the broad planks of the painted floor and on

the strong polished surfaces of the ashen furniture and in which

unending fascination was exercised by the clock case that

contained grandfather's construction books and other rarities

(new year's pistol, old knives, etc., etc.) by the old pictures

of relatives above the sofa; the lumber room upstairs with the

home made lute that belonged to a musical great-uncle who died

young (Ernst Ludwig) and with grandfather's false teeth; the

baking room in the adjoining bake-house into which the father

when a boy would retire with his violin in order not to burden

the grandmother with his `silly noise'; the attic below the

boarded tiled roof which contained all sorts of old pots to

collect the rain that seeped through in various places when the

weather was wet (grandmother could not be persuaded to prevent

the greatest part of the damage by having a few new tiles put on

the roof), the deep vaulted cellar lit by two holes in the wall,

the mice's abode (grandmother did not own a cat, probably because

she resented having to give up some of the milk to the animal),

access to which was by a completely dark, stone staircase without

handrail and in whose entry there stood a dusty little bottle

that father had filled with Easter Water from the Lonau some time

in the sixties; the little garden on the slope between the house

and the brook with its ancient, tempting pear tree and the wild

hop whips; the village brook whose rushing noise would send the

boy to sleep in the evening and wake him up in the morning; the

steep, high meadow behind the house with its path from which the

talented, adventurous great uncle, Heinrich Philipp, the joiner,

waved for the last time when on his way to Osterode in order to

set off on his big voyage to Australia from there, never to be

seen again. Now the timber frame of the dear house that had been

blackened by age has been covered with wood all around and has

been painted and has acquired quite a different appearance. August Topperwien

* * * * * * * * * *

The Heinrich Philipp mentioned in the last paragraph is the

grandfather of Ivy May Topperwien and great grandfather of Eldon

Fox. Annemarie Topperwien in Germany also wrote to me the

following in 1995:- According to our family tree all news of him

[Heinrich Philipp] ends after this point, but there is one

wonderful Tobacco case on inlaid work made by him and

respectfully given from father to son for the last 100 years.

Until now we didn't know anything about this skilful craftsman.

That there is a considerable family [in Australia] too we learned

just now by your letter.

It would seem also from the mention in the above account of the

handmade lute and the violin with its `silly noise' that the

grandmother did not like, that there has always been an interest

in and love of music in the Topperwien family. This has been

carried on now in almost every branch of the Australian

Topperwiens.

|